Today in Kimberley's History

|

|

|

|

66 days since beginning of the Siege of Kimberley, 1899

Extract from "The Diary of a Doctor's Wife – During the Siege of Kimberley October 1899 to February 1900" by Winifred Heberden.

Very early this morning all our available Mounted Men with some artillery made a reconnaissance along the Free State border towards the Boer position at Olifantsfontein, to find out the position of their guns, etc. We were fired on at a distance of 2 000 yards, and at 8 000 by the enemy's 9-pounder, the shells dropping in among our men, but harmlessly, owing to the soft sand. The Boers might, however, have supposed that some men were wounded as a dash was always made for the pieces as soon as the shell burst.

Our guns replied in their turn - to the joy of the numerous dogs that always accompany them on these occasions. The Pointers remain by the Maxims which have a somewhat more sporting sound than the 7-pounders; but they (the Pointers) seem to expect game to fall from the skies. When the men lie down to fire their rifles, the dogs lie down, too. In the course of the ride out several hares got up which the dogs and a few of the men were unable to resist, and some good sport was seen. A small bag which, nevertheless, must have been a welcome addition to the siege soup at the Trooper's Mess.

Owing to the struggle for meat every morning, orders have been issued that no person is to be served before 8 a.m. Only about four butcher's shops keep open for the sale of meat, so often the struggle is terrible, and as the best parts are put on one side for the Hospital, the Camp, and the Hotels, housekeepers come badly off at the end of the struggle, and often go away day after day without getting any at all. Tea and coffee are running short, these and breadstuffs, as well as meat are now controlled by the Military. Whiskey and cigarettes are nearly finished; whilst tinned milk has for some time been only obtainable through a doctor's certificate - and that at the rate of one tin only for each permit.

Extract from "The Diary of a Doctor's Wife – During the Siege of Kimberley October 1899 to February 1900" by Winifred Heberden.

Very early this morning all our available Mounted Men with some artillery made a reconnaissance along the Free State border towards the Boer position at Olifantsfontein, to find out the position of their guns, etc. We were fired on at a distance of 2 000 yards, and at 8 000 by the enemy's 9-pounder, the shells dropping in among our men, but harmlessly, owing to the soft sand. The Boers might, however, have supposed that some men were wounded as a dash was always made for the pieces as soon as the shell burst.

Our guns replied in their turn - to the joy of the numerous dogs that always accompany them on these occasions. The Pointers remain by the Maxims which have a somewhat more sporting sound than the 7-pounders; but they (the Pointers) seem to expect game to fall from the skies. When the men lie down to fire their rifles, the dogs lie down, too. In the course of the ride out several hares got up which the dogs and a few of the men were unable to resist, and some good sport was seen. A small bag which, nevertheless, must have been a welcome addition to the siege soup at the Trooper's Mess.

Owing to the struggle for meat every morning, orders have been issued that no person is to be served before 8 a.m. Only about four butcher's shops keep open for the sale of meat, so often the struggle is terrible, and as the best parts are put on one side for the Hospital, the Camp, and the Hotels, housekeepers come badly off at the end of the struggle, and often go away day after day without getting any at all. Tea and coffee are running short, these and breadstuffs, as well as meat are now controlled by the Military. Whiskey and cigarettes are nearly finished; whilst tinned milk has for some time been only obtainable through a doctor's certificate - and that at the rate of one tin only for each permit.

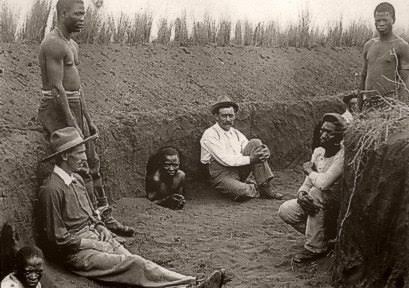

Disease and starvation disproportionately kills blacks during the Siege of Kimberley - 1899

Rationing of foodstuffs was not seriously adhered to until the military authorities realized that the siege of Kimberley would not be lifted before Christmas 1899, and a proclamation was issued on 20 December 1899 in that all basic foodstuffs were taken over by the military. Rationing was implemented, complete with ration tickets, and by January 1900 the entire population was on fixed rations, the whites and coloureds receiving the most, then the Indians, with the Blacks receiving the least. Whites and coloureds (per person), would receive a daily allowance of 14 ounces of bread or 10 ounces of Boer meal and flour, two ounces of either mealies or corn, two ounces of rice, 2 ounces of sugar, ¼ ounce of tea, and a half ounce of coffee. Meat was a half pound per diem. Indians were allowed two ounces of mealie meal, 8 ounces of rice, and the same tea, coffee and sugar allowance as the whites. Blacks would receive six ounces of mealie meal, four ounces of corn, two ounces of samp, and tea, coffee and sugar the same as the others. The mine workers would be fed by the mining company.

In fact, at one stage there was a mutiny in the mine compounds as the Blacks within vociferously objected to only receiving one tablespoonful of mealie meal per day. The regular soldiers from the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment were called out and surrounded the compound with fixed bayonets until the uprising subsided. In middle January 1900 each householder had to register the name of every black person living on their property, and get a certificate for each one. Only those with certificates could get food. There was much complaining about the rations in the columns of the Diamond Fields Advertiser, particularly from the blacks, and theft of food became common because of starvation. The lack of basic dietary requirements for the Blacks ensured that disease and death was not far off. Disease ran rampant through the compounds, refugee camp, and townships, and in particular, scurvy. 592 blacks died from this disease during January and up to 15 February 1900, and the six weeks following the siege. Not one white died from scurvy. Other diseases that led to deaths were infantile diarrhoea, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and dysentery.

The chief cause of death during the siege among the blacks was disease. As stated, scurvy was the main cause, followed by infantile diarrhoea and pneumonia. Pneumonia and Tubercolosis were mostly prevalent in the mine compounds. Total black deaths during the siege and immediate aftermath (14 October 1899- 28 February 1900) amounted to 1648. Total deaths from disease in all races during the same period was 1679. It is fairly certain that more died than is officially recorded. Most frightening is the fact that the death rate for black babies was 935 out of every 1000.

The shelling of the town by the Boers accounted for only two known black deaths during the siege, despite the fact that about 8500 shells fell in Kimberley during the siege, including many that fell in the black refugee camp at the racecourse, and even in the mine compounds.

(Courtesy Steve Lunderstedt, Kimberley Calls...and Recalls)

Rationing of foodstuffs was not seriously adhered to until the military authorities realized that the siege of Kimberley would not be lifted before Christmas 1899, and a proclamation was issued on 20 December 1899 in that all basic foodstuffs were taken over by the military. Rationing was implemented, complete with ration tickets, and by January 1900 the entire population was on fixed rations, the whites and coloureds receiving the most, then the Indians, with the Blacks receiving the least. Whites and coloureds (per person), would receive a daily allowance of 14 ounces of bread or 10 ounces of Boer meal and flour, two ounces of either mealies or corn, two ounces of rice, 2 ounces of sugar, ¼ ounce of tea, and a half ounce of coffee. Meat was a half pound per diem. Indians were allowed two ounces of mealie meal, 8 ounces of rice, and the same tea, coffee and sugar allowance as the whites. Blacks would receive six ounces of mealie meal, four ounces of corn, two ounces of samp, and tea, coffee and sugar the same as the others. The mine workers would be fed by the mining company.

In fact, at one stage there was a mutiny in the mine compounds as the Blacks within vociferously objected to only receiving one tablespoonful of mealie meal per day. The regular soldiers from the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment were called out and surrounded the compound with fixed bayonets until the uprising subsided. In middle January 1900 each householder had to register the name of every black person living on their property, and get a certificate for each one. Only those with certificates could get food. There was much complaining about the rations in the columns of the Diamond Fields Advertiser, particularly from the blacks, and theft of food became common because of starvation. The lack of basic dietary requirements for the Blacks ensured that disease and death was not far off. Disease ran rampant through the compounds, refugee camp, and townships, and in particular, scurvy. 592 blacks died from this disease during January and up to 15 February 1900, and the six weeks following the siege. Not one white died from scurvy. Other diseases that led to deaths were infantile diarrhoea, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and dysentery.

The chief cause of death during the siege among the blacks was disease. As stated, scurvy was the main cause, followed by infantile diarrhoea and pneumonia. Pneumonia and Tubercolosis were mostly prevalent in the mine compounds. Total black deaths during the siege and immediate aftermath (14 October 1899- 28 February 1900) amounted to 1648. Total deaths from disease in all races during the same period was 1679. It is fairly certain that more died than is officially recorded. Most frightening is the fact that the death rate for black babies was 935 out of every 1000.

The shelling of the town by the Boers accounted for only two known black deaths during the siege, despite the fact that about 8500 shells fell in Kimberley during the siege, including many that fell in the black refugee camp at the racecourse, and even in the mine compounds.

(Courtesy Steve Lunderstedt, Kimberley Calls...and Recalls)