Today in Kimberley's History

|

|

|

|

Kimberley’s Big Hole discovered - 1871

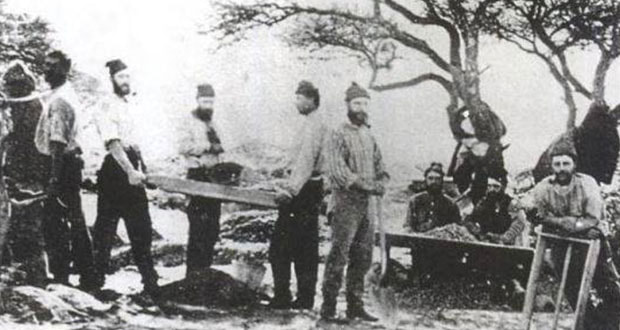

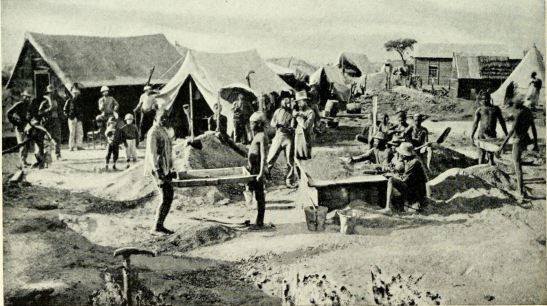

Before the acknowledged Rush in July 1871 which saw Colesberg Kopje (also named Gilfillan’s Kop as well as the New Rush) mine discovered, the owner of the farm Vooruitzicht, Johannes Nicolaas de Beer, had been prospecting in the area “for some time at odd intervals.” Historian George Beet himself does not commit to whom the discoverer is, or was, but he does state that the Mine was discovered on or about the 16 July and then rushed on 18 July 1871. T.B. Kisch wrote that while he was working at Bultfontein mine he had in his employ an elderly Griqua man who stated that while feeding his oxen on a stretch of rising ground (Colesberg kopje) he noticed that the ground was very similar to the soil being worked at the De Beers Mine some 1 mile east of that position. Kisch and four others (including two black employees) then made their way to the kopje and sank a shaft some four feet deep but without finding any diamonds. Kisch goes on to say that Fleetwood Rawstorne visited him that same day and asked how it was going and he told Rawstorne exactly what had happened, in effect, nothing. Rawstorne proposed that he send an employee of his to continue digging in that spot, which was agreed to, and Kisch sent his black employee Abel to point out the spot where the shaft had been sunk.

Three days later, on the 17th July 1871, according to Kisch, Rawstorne’s employee discovered a diamond in the shaft. Beet states that the date the diamond was discovered was Sunday 16th July 1871, although Henry Richard Giddy, a member of Rawstorne’s Colesberg party, states that it was on Saturday 15th July 1871. All the other members of the Colesberg party state that it was discovered on the Sunday, so Giddy is somewhat outvoted by 7 to 1. This majority decision is why George Beet decided that the mine was discovered on the 16th rather than the 15th July 1871. What is certain is that by the 18th July when Rawstorne reported his find, Colesberg Kopje was “rushed”.

Sidney Mendelssohn, another Kimberley pioneer, states that it was actually Kisch and three others that discovered the Big Hole. Giddy, who was there while Mendelssohn was not, refutes this, stating that seven young men (and all members of Rawstorne’s party) were allowed to register their claims first after Rawstorne had done so; and that Kisch, being part of Rawstorne’s camp at the De Beers mine, may well have secured claims in Colesberg Kopje, but only later and definitely after Rawstorne. Fleetwood Rawstorne and his party hold the key to the discovery. Why was it named Colesberg Kopje, and why was Rawstorne’s party the first to register claims on the land? If it had been anybody else who discovered the first diamond, the mine would surely have been named something else?

Indeed, Kisch, Giddy and Rawstorne, all agree that it was Rawstorne’s party that found the first diamond. It must also be considered a fact that there were many prospectors digging all around the region before the first diamond was discovered. Even Giddy agrees that there were many abandoned shafts dotted all around “where previous prospectors had evidently been trying their luck, but without success.” If this is the case, then the discoverer of the first diamond was definitely the so-called Cape Coloured “boy” Damon, the employee of Fleetwood Rawstorne. Giddy states that Damon was the Red Cap (Colesberg party) party cook, and being rather susceptible to alcohol, had been ordered out of the camp by Rawstorne to sink a shaft and look for diamonds.

Damon had found three diamonds in a shaft some ten to twelve feet deep according to Giddy. Damon led the entire Red Cap party to the area, and all their claims surrounded the shaft dug by Damon. Kisch also states that it was the employee of Rawstorne that found the first diamond. Rawstorne himself says that Damon found the diamond.

Gardner Williams writes that “the story generally accepted is that the first diamond discovered on Colesberg Kopje was picked up by a coloured servant of Fleetwood Rawstorne…”

Therefore it can quite safely be said that Damon, the employee of Fleetwood Rawstorne, based on the information available to us today, was the person who discovered the Big Hole as we know it. It was he, even though he may well have dug in someone else’s shaft, that actually found the diamond that saw Rawstorne and his party scurrying to Colesberg Kopje shortly before the biggest “rush” the world has ever seen. That Rawstorne received credit over the last century and a bit can be attributed to the fact that Damon worked for Rawstorne.

Likewise, the name of the mine, registered initially as Colesberg Kopje by Rawstorne and his party, was known to everyone else as the De Beers New Rush. It eventually became known as the Kimberley Mine and today is better known as the Big Hole of Kimberley.

This entire story only really has one unanswered question: Who was this mysterious Damon? This has really confused everyone since the discovery of the Kimberley Mine, and it was only recently that a short (and published) story came to light in the Kimberley Africana Library archives.

The story published in the South African Digest of July 1974 is an interview with Solomon Demoense (also spelled Damoense in certain accounts), an alluvial diamond digger who had operated in the Barkly West area for 43 years. Solomon related to the writer, J.H. Deacon, that his father, Esau Demoense, “…had two claims to fame. He helped to make the wagons that conveyed the diggers to Kimberley during the old diamond rush days, and he found the first diamond at Kimberley’s Big Hole. It wasn’t a hole then, it was a high hill called Colesberg Kopje.” Esau Demoense had been employed with a wagon maker at Paarl, and had made his way up to the diamond diggings in 1871 to seek his fame and fortune. He died in 1940, aged 104 years, making him 35 years old at the time of the discovery. The whole oral history tale as related by Solomon Demoense tallies with both primary and secondary historical sources, and Esau’s surname is so close to “Damon” that it can only but be believed. To Esau Demoense then, must go the credit of the discovery of the world famous Big Hole of Kimberley.

Article by Steve Lunderstedt, Kimberley Calls... and Recalls Facebook group

Before the acknowledged Rush in July 1871 which saw Colesberg Kopje (also named Gilfillan’s Kop as well as the New Rush) mine discovered, the owner of the farm Vooruitzicht, Johannes Nicolaas de Beer, had been prospecting in the area “for some time at odd intervals.” Historian George Beet himself does not commit to whom the discoverer is, or was, but he does state that the Mine was discovered on or about the 16 July and then rushed on 18 July 1871. T.B. Kisch wrote that while he was working at Bultfontein mine he had in his employ an elderly Griqua man who stated that while feeding his oxen on a stretch of rising ground (Colesberg kopje) he noticed that the ground was very similar to the soil being worked at the De Beers Mine some 1 mile east of that position. Kisch and four others (including two black employees) then made their way to the kopje and sank a shaft some four feet deep but without finding any diamonds. Kisch goes on to say that Fleetwood Rawstorne visited him that same day and asked how it was going and he told Rawstorne exactly what had happened, in effect, nothing. Rawstorne proposed that he send an employee of his to continue digging in that spot, which was agreed to, and Kisch sent his black employee Abel to point out the spot where the shaft had been sunk.

Three days later, on the 17th July 1871, according to Kisch, Rawstorne’s employee discovered a diamond in the shaft. Beet states that the date the diamond was discovered was Sunday 16th July 1871, although Henry Richard Giddy, a member of Rawstorne’s Colesberg party, states that it was on Saturday 15th July 1871. All the other members of the Colesberg party state that it was discovered on the Sunday, so Giddy is somewhat outvoted by 7 to 1. This majority decision is why George Beet decided that the mine was discovered on the 16th rather than the 15th July 1871. What is certain is that by the 18th July when Rawstorne reported his find, Colesberg Kopje was “rushed”.

Sidney Mendelssohn, another Kimberley pioneer, states that it was actually Kisch and three others that discovered the Big Hole. Giddy, who was there while Mendelssohn was not, refutes this, stating that seven young men (and all members of Rawstorne’s party) were allowed to register their claims first after Rawstorne had done so; and that Kisch, being part of Rawstorne’s camp at the De Beers mine, may well have secured claims in Colesberg Kopje, but only later and definitely after Rawstorne. Fleetwood Rawstorne and his party hold the key to the discovery. Why was it named Colesberg Kopje, and why was Rawstorne’s party the first to register claims on the land? If it had been anybody else who discovered the first diamond, the mine would surely have been named something else?

Indeed, Kisch, Giddy and Rawstorne, all agree that it was Rawstorne’s party that found the first diamond. It must also be considered a fact that there were many prospectors digging all around the region before the first diamond was discovered. Even Giddy agrees that there were many abandoned shafts dotted all around “where previous prospectors had evidently been trying their luck, but without success.” If this is the case, then the discoverer of the first diamond was definitely the so-called Cape Coloured “boy” Damon, the employee of Fleetwood Rawstorne. Giddy states that Damon was the Red Cap (Colesberg party) party cook, and being rather susceptible to alcohol, had been ordered out of the camp by Rawstorne to sink a shaft and look for diamonds.

Damon had found three diamonds in a shaft some ten to twelve feet deep according to Giddy. Damon led the entire Red Cap party to the area, and all their claims surrounded the shaft dug by Damon. Kisch also states that it was the employee of Rawstorne that found the first diamond. Rawstorne himself says that Damon found the diamond.

Gardner Williams writes that “the story generally accepted is that the first diamond discovered on Colesberg Kopje was picked up by a coloured servant of Fleetwood Rawstorne…”

Therefore it can quite safely be said that Damon, the employee of Fleetwood Rawstorne, based on the information available to us today, was the person who discovered the Big Hole as we know it. It was he, even though he may well have dug in someone else’s shaft, that actually found the diamond that saw Rawstorne and his party scurrying to Colesberg Kopje shortly before the biggest “rush” the world has ever seen. That Rawstorne received credit over the last century and a bit can be attributed to the fact that Damon worked for Rawstorne.

Likewise, the name of the mine, registered initially as Colesberg Kopje by Rawstorne and his party, was known to everyone else as the De Beers New Rush. It eventually became known as the Kimberley Mine and today is better known as the Big Hole of Kimberley.

This entire story only really has one unanswered question: Who was this mysterious Damon? This has really confused everyone since the discovery of the Kimberley Mine, and it was only recently that a short (and published) story came to light in the Kimberley Africana Library archives.

The story published in the South African Digest of July 1974 is an interview with Solomon Demoense (also spelled Damoense in certain accounts), an alluvial diamond digger who had operated in the Barkly West area for 43 years. Solomon related to the writer, J.H. Deacon, that his father, Esau Demoense, “…had two claims to fame. He helped to make the wagons that conveyed the diggers to Kimberley during the old diamond rush days, and he found the first diamond at Kimberley’s Big Hole. It wasn’t a hole then, it was a high hill called Colesberg Kopje.” Esau Demoense had been employed with a wagon maker at Paarl, and had made his way up to the diamond diggings in 1871 to seek his fame and fortune. He died in 1940, aged 104 years, making him 35 years old at the time of the discovery. The whole oral history tale as related by Solomon Demoense tallies with both primary and secondary historical sources, and Esau’s surname is so close to “Damon” that it can only but be believed. To Esau Demoense then, must go the credit of the discovery of the world famous Big Hole of Kimberley.

Article by Steve Lunderstedt, Kimberley Calls... and Recalls Facebook group

British Colonial Office appoints a Ladies Commission to investigate concentration camps in South Africa - 1901

On 16 July 1901, the Ladies commission was appointed. The members who were considered impartial were, Mrs. Millicent G. Fawcett, Emily Hobhouse and Dr. Jane Waterson. They were appointed by the British Office to investigate the concentration camps in South Africa during the Second Anglo Boer War. The camps were found to have been inadequately built and maintained, unclean, and overcrowded. These factors contributed to the spread of disease. There was a shortage of both medical supplies and medical staff. At least 25 000 children and women died from epidemics of dysentery, measles, and enteric fever. Emily Hobhouse visited the camps to try and improve the life of the prisoners living on the concentration camps. Hobhouse was an English philanthropist and social worker who tried her best to make the British authorities aware of the plight of women and children in these inhumane conditions. Due to the publicising of what was occurring in the concentration camps international opinion turned against the British, and critics were outspoken about their disdain and disgust over the situation. This led to the British General Kitchener changing and ceasing the practice of imprisoning women and children in the camps.

On 16 July 1901, the Ladies commission was appointed. The members who were considered impartial were, Mrs. Millicent G. Fawcett, Emily Hobhouse and Dr. Jane Waterson. They were appointed by the British Office to investigate the concentration camps in South Africa during the Second Anglo Boer War. The camps were found to have been inadequately built and maintained, unclean, and overcrowded. These factors contributed to the spread of disease. There was a shortage of both medical supplies and medical staff. At least 25 000 children and women died from epidemics of dysentery, measles, and enteric fever. Emily Hobhouse visited the camps to try and improve the life of the prisoners living on the concentration camps. Hobhouse was an English philanthropist and social worker who tried her best to make the British authorities aware of the plight of women and children in these inhumane conditions. Due to the publicising of what was occurring in the concentration camps international opinion turned against the British, and critics were outspoken about their disdain and disgust over the situation. This led to the British General Kitchener changing and ceasing the practice of imprisoning women and children in the camps.

Legendary artist Johnny Clegg dies - 2019

On 16 July 2019, Jonny Clegg died at the age 66 years at his home in Johannesburg, Gauteng after he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2015. He is known as a songwriter, a dancer and an anthropologist. Clegg‘s music touched so many souls with its vibrant blend of Western pop and African Zulu rhythms. Clegg’s unique music style had an impact by embracing different cultures and enhanced the social cohesion of young South Africans. During his music career, he produced so many hits including Impi, Great Heart and African Sky Blue. In addition, he received a number of awards including being called a ‘Knight of Arts and Letters’ by the French Government in 1991. Clegg was nominated as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE). This veteran was also honoured with various doctorates including the Order of Ikhamanga. Jonny Clegg is survived by his wife Jenny and their two sons Jesse and Jaron.

On 16 July 2019, Jonny Clegg died at the age 66 years at his home in Johannesburg, Gauteng after he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2015. He is known as a songwriter, a dancer and an anthropologist. Clegg‘s music touched so many souls with its vibrant blend of Western pop and African Zulu rhythms. Clegg’s unique music style had an impact by embracing different cultures and enhanced the social cohesion of young South Africans. During his music career, he produced so many hits including Impi, Great Heart and African Sky Blue. In addition, he received a number of awards including being called a ‘Knight of Arts and Letters’ by the French Government in 1991. Clegg was nominated as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE). This veteran was also honoured with various doctorates including the Order of Ikhamanga. Jonny Clegg is survived by his wife Jenny and their two sons Jesse and Jaron.