Today in Kimberley's History

|

|

|

|

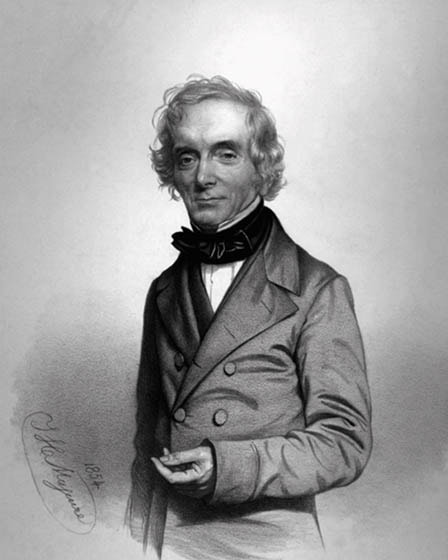

William J. Burchell, botanist and explorer of the South African interior, dies - 1863

William John Burchell is credited “with having been the most prolific collector of botanical and zoological specimens.” During a four-year scientific exploration of South Africa, he amassed a collection of over 63,000 specimens. And yet, Burchell’s contributions to science have been largely overlooked. As William Swainson bemoaned, “science must ever regret that one whose powers of mind were so varied…was so signally neglected in his own country.”

2015 marked the 200th anniversary of Burchell’s return to Cape Town following his four-year expedition in South Africa. The University of Pretoria recently digitized Burchell’s account of this journey, a two-volume work entitled Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa (1822-24) for BHL. This offers an excellent opportunity to not only highlight this recent addition from our colleagues in BHL Africa, but recognize the incredible accomplishments of a remarkable man.

William Burchell was born in Fulham, England, in 1781. His family owned the prosperous nine-and-a-half acre Fulham Nursery and Botanical Garden, which afforded him many opportunities to study botany and interact with some of the most influential natural historians of the day. Sir William Hooker, the first director of the Royal Gardens in Kew, was Burchell’s friend and mentor. The prosperity of his family’s business provided Burchell with the means to travel and nurture his interest in natural history and particularly botany.

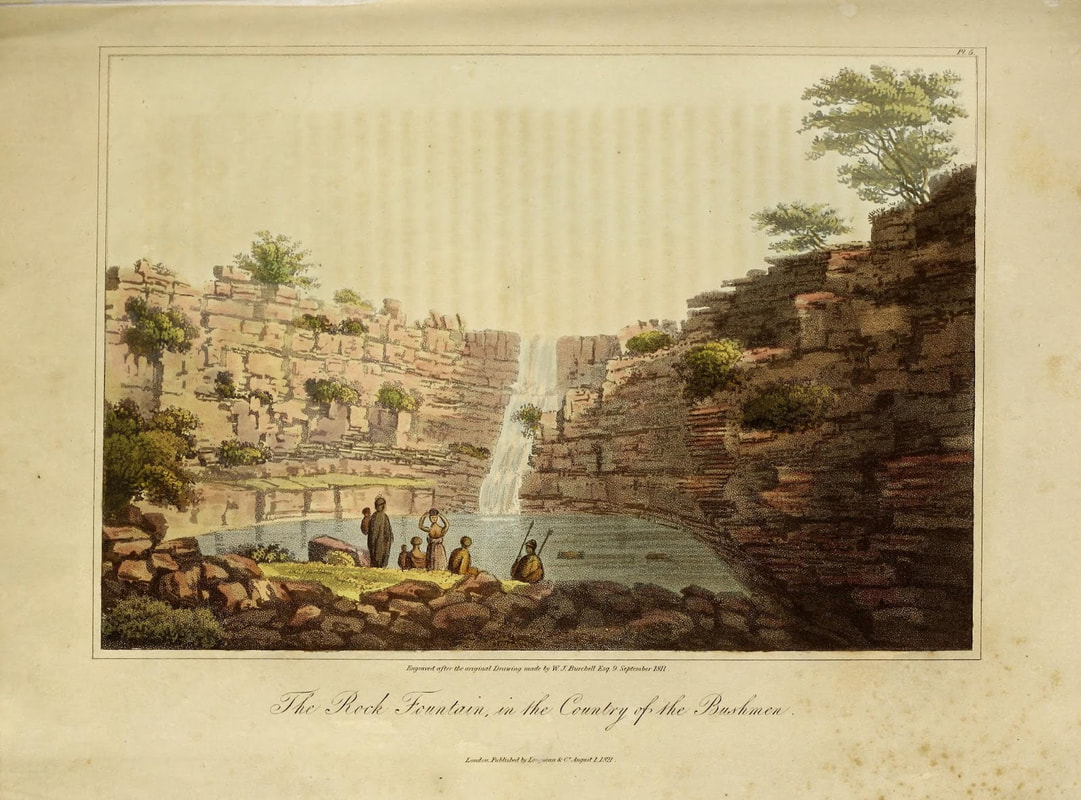

In 1810, Burchell arrived in Cape Town, South Africa, and on 19 June 1811, he set out from that city on a four-year expedition throughout the interior of southern Africa “solely for the purpose of acquiring knowledge.” During the journey, he covered 7,000 km, mostly in an ox-wagon that he designed to serve as his home, laboratory, and library. He traveled as far north-east as the asbestos mountains just north of Chue Spring and became the first recorded European explorer to successfully travel through Bushmanland. The account of his expedition, Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa, covers only the period from his arrival in Cape Town through his departure from Litakun in August 1812.

Burchell’s accomplishments on the journey were extensive, particularly in the field of natural history. He collected 50,000 species of plants, seeds and bulbs, 10,000 specimens of insects, animal skins, skeletons, and fish, numerous anthropological artifacts, and created 500 drawings during the expedition. The Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew now holds a vast majority of Burchell’s extensive botanical collections. His journals document the precise location, morphological features, and habitat of the specimens he collected.

In addition to natural history, Burchell made important observations in the earth sciences during the expedition, being the first recorded person to identify asbestos in the Northern Cape and the “first to describe glacial pavements in the country.” He also charted his entire route, creating a “Map of the Extratropical Parts of Southern Africa” (published in v.1 of his book), which was a “milestone in the cartography of the country.” In the field of astronomy, he observed the variability of Eta Carinae’s brightness, and, by using a combination of Friar’s Balsam (Compound Tincture Benzoin), laudanum, Buchu vinegar, and Wild Wormwood to treat a serious gunshot wound afflicting one of the expedition’s members, became the first recorded person to successfully integrate indigenous herbal medicine with medicines used in Europe “into the management of such a serious condition.”

After Burchell’s return to Cape Town in April 1815, he went on to travel in Brazil, collecting over 23,000 additional specimens. However, after his return to England, Burchell became increasingly reclusive and protective of his collections, focusing on cataloging his vast botanical specimens but also refusing to allow others to access his collections. Some historians hypothesize that he may have suffered from a bipolar-type disorder. In 1863, at the age of 82, after one unsuccessful suicide attempt by gunshot, he hung himself in a small outhouse in his garden. He is buried near his home in Fulham, in the family tomb at All Saints Church, Hammersmith.

Though his life had a tragic ending, Burchell’s accomplishments are remarkable. In addition to the many specimens he collected, a species of South African wild pomegranate (Burchellia bubalina) is named after him, and the common names of many animals bear his moniker, including Burchell’s zebra, Burchell’s coucal, three birds (Burchell’s starling, coarser, and grouse), a lizard (Burchell’s sand lizard), and the white rhinoceros (for which Burchell was the first to give a scientific name and is also known, although less-commonly, as Burchell’s rhinoceros). He also recommended the establishment of a public garden in Cape Town. He described the Kirstenbosch area as “the most picturesque I had seen in the vicinity.” The Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden was founded in 1913.

Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library

Digitised copy of Original publication by Burchell: Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa (1822-24)

William John Burchell is credited “with having been the most prolific collector of botanical and zoological specimens.” During a four-year scientific exploration of South Africa, he amassed a collection of over 63,000 specimens. And yet, Burchell’s contributions to science have been largely overlooked. As William Swainson bemoaned, “science must ever regret that one whose powers of mind were so varied…was so signally neglected in his own country.”

2015 marked the 200th anniversary of Burchell’s return to Cape Town following his four-year expedition in South Africa. The University of Pretoria recently digitized Burchell’s account of this journey, a two-volume work entitled Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa (1822-24) for BHL. This offers an excellent opportunity to not only highlight this recent addition from our colleagues in BHL Africa, but recognize the incredible accomplishments of a remarkable man.

William Burchell was born in Fulham, England, in 1781. His family owned the prosperous nine-and-a-half acre Fulham Nursery and Botanical Garden, which afforded him many opportunities to study botany and interact with some of the most influential natural historians of the day. Sir William Hooker, the first director of the Royal Gardens in Kew, was Burchell’s friend and mentor. The prosperity of his family’s business provided Burchell with the means to travel and nurture his interest in natural history and particularly botany.

In 1810, Burchell arrived in Cape Town, South Africa, and on 19 June 1811, he set out from that city on a four-year expedition throughout the interior of southern Africa “solely for the purpose of acquiring knowledge.” During the journey, he covered 7,000 km, mostly in an ox-wagon that he designed to serve as his home, laboratory, and library. He traveled as far north-east as the asbestos mountains just north of Chue Spring and became the first recorded European explorer to successfully travel through Bushmanland. The account of his expedition, Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa, covers only the period from his arrival in Cape Town through his departure from Litakun in August 1812.

Burchell’s accomplishments on the journey were extensive, particularly in the field of natural history. He collected 50,000 species of plants, seeds and bulbs, 10,000 specimens of insects, animal skins, skeletons, and fish, numerous anthropological artifacts, and created 500 drawings during the expedition. The Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew now holds a vast majority of Burchell’s extensive botanical collections. His journals document the precise location, morphological features, and habitat of the specimens he collected.

In addition to natural history, Burchell made important observations in the earth sciences during the expedition, being the first recorded person to identify asbestos in the Northern Cape and the “first to describe glacial pavements in the country.” He also charted his entire route, creating a “Map of the Extratropical Parts of Southern Africa” (published in v.1 of his book), which was a “milestone in the cartography of the country.” In the field of astronomy, he observed the variability of Eta Carinae’s brightness, and, by using a combination of Friar’s Balsam (Compound Tincture Benzoin), laudanum, Buchu vinegar, and Wild Wormwood to treat a serious gunshot wound afflicting one of the expedition’s members, became the first recorded person to successfully integrate indigenous herbal medicine with medicines used in Europe “into the management of such a serious condition.”

After Burchell’s return to Cape Town in April 1815, he went on to travel in Brazil, collecting over 23,000 additional specimens. However, after his return to England, Burchell became increasingly reclusive and protective of his collections, focusing on cataloging his vast botanical specimens but also refusing to allow others to access his collections. Some historians hypothesize that he may have suffered from a bipolar-type disorder. In 1863, at the age of 82, after one unsuccessful suicide attempt by gunshot, he hung himself in a small outhouse in his garden. He is buried near his home in Fulham, in the family tomb at All Saints Church, Hammersmith.

Though his life had a tragic ending, Burchell’s accomplishments are remarkable. In addition to the many specimens he collected, a species of South African wild pomegranate (Burchellia bubalina) is named after him, and the common names of many animals bear his moniker, including Burchell’s zebra, Burchell’s coucal, three birds (Burchell’s starling, coarser, and grouse), a lizard (Burchell’s sand lizard), and the white rhinoceros (for which Burchell was the first to give a scientific name and is also known, although less-commonly, as Burchell’s rhinoceros). He also recommended the establishment of a public garden in Cape Town. He described the Kirstenbosch area as “the most picturesque I had seen in the vicinity.” The Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden was founded in 1913.

Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library

Digitised copy of Original publication by Burchell: Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa (1822-24)

South African Communist Party leader Bram Fischer is sentenced to life imprisonment on charges of communism - 1966

During the 1940s, Bram Fischer served on the Johannesburg District Committee and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of South Africa (later SACP). In 1943, he helped A. B. Xuma revise the African National Congress (ANC) constitution, and was charged with incitement during the mineworkers' strike in 1946. He was also a member of the Congress of Democrats and formed part of the defence team for the leaders of the movement during the Treason Trial of 1956 to 1961. He also defended the accused during the Rivonia Trial in 1964. It was inevitable that his involvement with anti-Apartheid activists and his dedication to the SACP would implicate him in illegal activities.

In September 1964, Fischer was arrested and charged with being a member of the Communist Party - a banned organisation. He was granted bail, and in January 1965 he went underground. He was only recaptured in November of that year. On 23 March 1966, he was found guilty of violating the Suppression of Communism Act and conspiring to commit sabotage. These convictions lead to a sentence of life imprisonment in Pretoria Central Prison. In 1967, he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize. During his incarceration, he contracted cancer. A fall induced by the effects of the cancer in September 1974 left Fischer with a fractured neck femur, which left him partially paralysed and unable to talk. It was not until December of that year that the authorities transferred him to a hospital. When news of his illness was publicised, the public lobbied government for his release. Fischer was then placed under house arrest at his brother's home in Bloemfontein in April 1975, and died a few weeks later. The prison had Fischer's ashes returned to them after the funeral, and have therefore never been found.

During the 1940s, Bram Fischer served on the Johannesburg District Committee and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of South Africa (later SACP). In 1943, he helped A. B. Xuma revise the African National Congress (ANC) constitution, and was charged with incitement during the mineworkers' strike in 1946. He was also a member of the Congress of Democrats and formed part of the defence team for the leaders of the movement during the Treason Trial of 1956 to 1961. He also defended the accused during the Rivonia Trial in 1964. It was inevitable that his involvement with anti-Apartheid activists and his dedication to the SACP would implicate him in illegal activities.

In September 1964, Fischer was arrested and charged with being a member of the Communist Party - a banned organisation. He was granted bail, and in January 1965 he went underground. He was only recaptured in November of that year. On 23 March 1966, he was found guilty of violating the Suppression of Communism Act and conspiring to commit sabotage. These convictions lead to a sentence of life imprisonment in Pretoria Central Prison. In 1967, he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize. During his incarceration, he contracted cancer. A fall induced by the effects of the cancer in September 1974 left Fischer with a fractured neck femur, which left him partially paralysed and unable to talk. It was not until December of that year that the authorities transferred him to a hospital. When news of his illness was publicised, the public lobbied government for his release. Fischer was then placed under house arrest at his brother's home in Bloemfontein in April 1975, and died a few weeks later. The prison had Fischer's ashes returned to them after the funeral, and have therefore never been found.