Today in Kimberley's History

|

|

|

|

Title deeds to the farm Dorstfontein granted to AP du Toit, 1860

The first of the Kimberley diamond mines to be discovered was the Dutoitspan Mine, named such because the farm Dorstfontein originally belonged to Abraham Paulus du Toit, who had built a small house next door to the Pan, a saucepan shaped depression that holds water. It was named Du Toit’s Pan for obvious reasons. Du Toit sold the farm to a Mr Geyer for £525 on 12 May 1865, and he in turn sold it to Adriaan J. van Wyk for £870 on 6 January 1869. At the time of the discovery the owner was Adriaan J. van Wyk. Early Kimberley historian George Beet states that van Wyk found some “pretty stones” while digging a well, and these he sold to a “travelling Jew”. Given that Van Wyk never knew the value of the stones or the man of the Jewish faith, does the credit for the discovery of the mine go to van Wyk or to the “travelling Jew”? And who is this “travelling Jew”?

In Jeremy Lawrence’s biography on Joseph Benjamin Robinson, it is stated that in either 1868 or possibly even in 1869 – the original details are somewhat sketchy – Robinson, while on his way to Hebron, now Windsorton, heard that a farmer’s wife had a stone similar to what he was looking for. He went to see the farmer’s wife, a Mrs van Wyk of Dorstfontein, and purchased the diamond from her. She had found it in a dry donga close to the house. Another tale told by J.B. Robinson was that she sold him two bottles of pretty stones, among which were six or eight diamonds for which he paid her four sovereigns. Robinson further states that during this same journey he shot a springbok antelope on the farmer de Beer’s land, the farm Vooruitzicht. De Beer, a near neighbour of the van Wyk’s, also showed Robinson a diamond that he had picked up under the tree where the antelope had been shot. Robinson claimed that this exact spot was where the De Beers mine was later discovered, although we only have his word for it. Was this “travelling Jew” perhaps Joseph Benjamin Robinson? As neither Mr and Mrs van Wyk, nor J.B. Robinson, actually laid claim to the land as genuine diggers, and with the van Wyk’s not realising that the pretty stones they had collected were actually diamonds, the claimant for discovery of the Dutoitspan Mine should not go to any of them. Who does the honour go to?

William Alderson, later the majority shareholder in the fledgling De Beers Mining Company made famous by Cecil Rhodes and Charles Rudd, before losing all his money in some disastrous ventures, at some time “…toward the end of 1869 and the beginning of 1870…heard that a farmer named van Wyk was giving out ground to Dutchmen on his farm, and that they were…finding diamonds.” Alderson and his group, including William Delaney, Robert Randall, Rowe (Natal), Salaman, Thomas Short, Hodges and Coffin, made their way to the farm and encamped, mainly as they had been advised that van Wyk would only allow ‘Dutchmen’ to dig on his farm. The group heard a rumour that at least 92 diamonds had been discovered – a false rumour – and rushed the kopje below which the ‘Dutchmen’ were searching for diamonds. The first mention in the South African newspapers on the diamond finds at Dutoitspan was a letter dated 4 November 1869 where it stated that in middle October five diamonds were picked up in 2-3 hours at “Tooispan.” Author Brian Roberts suggests that the first diamonds were discovered in early 1869 at Dutoitspan and by September the same year at Bultfontein. Fred Steytler, a clerk from Hopetown, stated that he had seen at least six diamonds found at Dutoitspan in October 1869 and that “diamonds are to be found in abundance.”

Certainly by December 1869 there were diggers at Dutoitspan, and the newspaper Diamond News, based at Klipdrift, stated that diamonds were being found at both Dutoitspan and Bultfontein from November 1869. By July 1870 there were a fair number of diggers operating their claims.

Alderson pegged out the first claim on the new diggings of Dutoitspan, the rest of his group following suit, and in his reminiscences, Alderson stated that there were at least 200 ‘Dutchmen’ searching and digging at the base of the kopje. Following the lead of Alderson, they too rushed the kopje and laid their claims. Van Wyk, who was most unhappy about this state of affairs on his farm, could not really do anything about it, and after much discussion, was happy to accept 7/6 per claim per month from the diggers.

Van Wyk tried his best to sell his farm towards the end of 1870, even placing advertisements in newspapers proclaiming the value of the land. “For more than six months people have been digging…” stated one such advertisement, and the “…weekly finds average 60 – 100 diamonds…”

On 11 March 1871 the Dutoitspan farm was sold to Lilienfeld, Webb and partners (the London and South African Exploration Company) for £2600. The diamond controversy that followed and the Keate Award verdict of 1871 led to the annexation of the farms from the Orange Free State which became part of Griqualand West, which in turn was absorbed into the Cape Colony. So, is the discoverer of the Dutoitspan Mine William Alderson because he laid the first claim? Or is it the several hundred Dutch-speaking diggers who were already there before he arrived? Or perhaps it really is Joseph Robinson, but if it is he, then Mr and Mrs van Wyk must take some credit too, for it is they who actually found the first diamond, knowingly or not.

The first of the Kimberley diamond mines to be discovered was the Dutoitspan Mine, named such because the farm Dorstfontein originally belonged to Abraham Paulus du Toit, who had built a small house next door to the Pan, a saucepan shaped depression that holds water. It was named Du Toit’s Pan for obvious reasons. Du Toit sold the farm to a Mr Geyer for £525 on 12 May 1865, and he in turn sold it to Adriaan J. van Wyk for £870 on 6 January 1869. At the time of the discovery the owner was Adriaan J. van Wyk. Early Kimberley historian George Beet states that van Wyk found some “pretty stones” while digging a well, and these he sold to a “travelling Jew”. Given that Van Wyk never knew the value of the stones or the man of the Jewish faith, does the credit for the discovery of the mine go to van Wyk or to the “travelling Jew”? And who is this “travelling Jew”?

In Jeremy Lawrence’s biography on Joseph Benjamin Robinson, it is stated that in either 1868 or possibly even in 1869 – the original details are somewhat sketchy – Robinson, while on his way to Hebron, now Windsorton, heard that a farmer’s wife had a stone similar to what he was looking for. He went to see the farmer’s wife, a Mrs van Wyk of Dorstfontein, and purchased the diamond from her. She had found it in a dry donga close to the house. Another tale told by J.B. Robinson was that she sold him two bottles of pretty stones, among which were six or eight diamonds for which he paid her four sovereigns. Robinson further states that during this same journey he shot a springbok antelope on the farmer de Beer’s land, the farm Vooruitzicht. De Beer, a near neighbour of the van Wyk’s, also showed Robinson a diamond that he had picked up under the tree where the antelope had been shot. Robinson claimed that this exact spot was where the De Beers mine was later discovered, although we only have his word for it. Was this “travelling Jew” perhaps Joseph Benjamin Robinson? As neither Mr and Mrs van Wyk, nor J.B. Robinson, actually laid claim to the land as genuine diggers, and with the van Wyk’s not realising that the pretty stones they had collected were actually diamonds, the claimant for discovery of the Dutoitspan Mine should not go to any of them. Who does the honour go to?

William Alderson, later the majority shareholder in the fledgling De Beers Mining Company made famous by Cecil Rhodes and Charles Rudd, before losing all his money in some disastrous ventures, at some time “…toward the end of 1869 and the beginning of 1870…heard that a farmer named van Wyk was giving out ground to Dutchmen on his farm, and that they were…finding diamonds.” Alderson and his group, including William Delaney, Robert Randall, Rowe (Natal), Salaman, Thomas Short, Hodges and Coffin, made their way to the farm and encamped, mainly as they had been advised that van Wyk would only allow ‘Dutchmen’ to dig on his farm. The group heard a rumour that at least 92 diamonds had been discovered – a false rumour – and rushed the kopje below which the ‘Dutchmen’ were searching for diamonds. The first mention in the South African newspapers on the diamond finds at Dutoitspan was a letter dated 4 November 1869 where it stated that in middle October five diamonds were picked up in 2-3 hours at “Tooispan.” Author Brian Roberts suggests that the first diamonds were discovered in early 1869 at Dutoitspan and by September the same year at Bultfontein. Fred Steytler, a clerk from Hopetown, stated that he had seen at least six diamonds found at Dutoitspan in October 1869 and that “diamonds are to be found in abundance.”

Certainly by December 1869 there were diggers at Dutoitspan, and the newspaper Diamond News, based at Klipdrift, stated that diamonds were being found at both Dutoitspan and Bultfontein from November 1869. By July 1870 there were a fair number of diggers operating their claims.

Alderson pegged out the first claim on the new diggings of Dutoitspan, the rest of his group following suit, and in his reminiscences, Alderson stated that there were at least 200 ‘Dutchmen’ searching and digging at the base of the kopje. Following the lead of Alderson, they too rushed the kopje and laid their claims. Van Wyk, who was most unhappy about this state of affairs on his farm, could not really do anything about it, and after much discussion, was happy to accept 7/6 per claim per month from the diggers.

Van Wyk tried his best to sell his farm towards the end of 1870, even placing advertisements in newspapers proclaiming the value of the land. “For more than six months people have been digging…” stated one such advertisement, and the “…weekly finds average 60 – 100 diamonds…”

On 11 March 1871 the Dutoitspan farm was sold to Lilienfeld, Webb and partners (the London and South African Exploration Company) for £2600. The diamond controversy that followed and the Keate Award verdict of 1871 led to the annexation of the farms from the Orange Free State which became part of Griqualand West, which in turn was absorbed into the Cape Colony. So, is the discoverer of the Dutoitspan Mine William Alderson because he laid the first claim? Or is it the several hundred Dutch-speaking diggers who were already there before he arrived? Or perhaps it really is Joseph Robinson, but if it is he, then Mr and Mrs van Wyk must take some credit too, for it is they who actually found the first diamond, knowingly or not.

Primary information source courtesy of Kimberley Calls...and Recalls Facebook Group (except where otherwise stated)

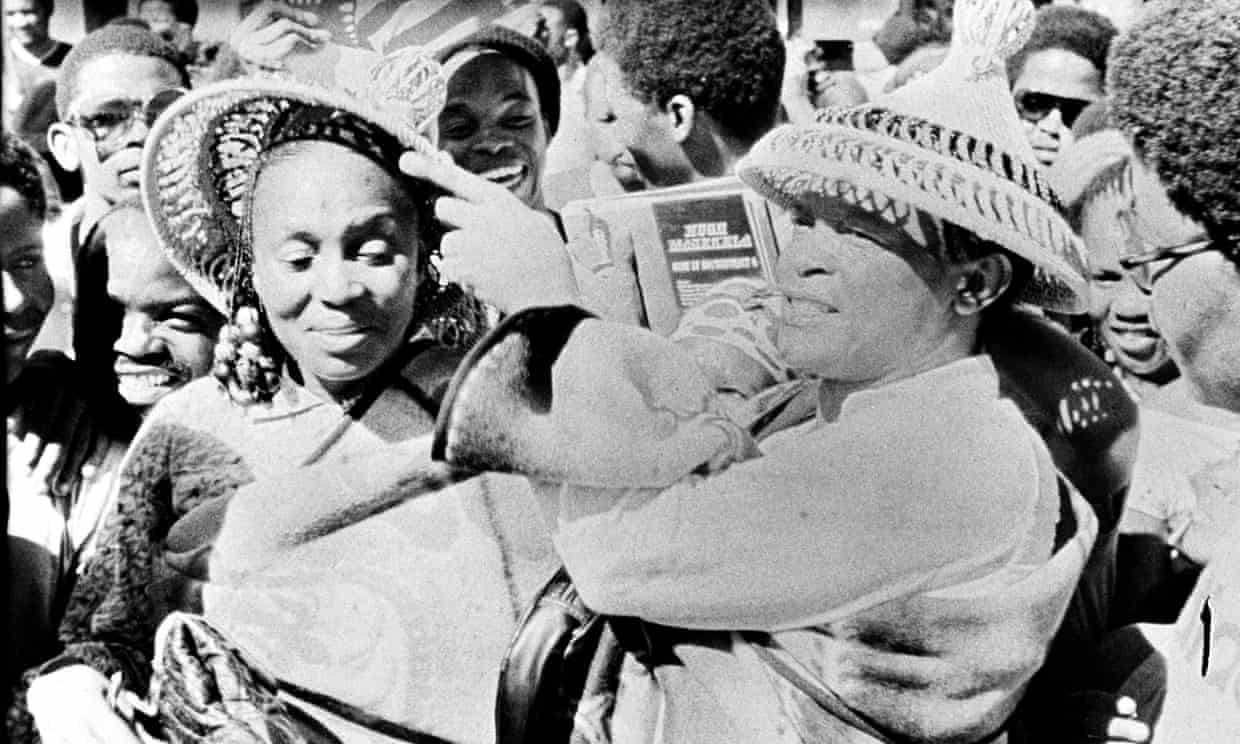

The father of South African Jazz, Hugh Masekela, born - 1939

Hugh Ramapolo Masekela was a South African trumpeter, flugelhornist, cornetist, singer and composer who has been described as "the father of South African jazz". Masekela was known for his jazz compositions and for writing well-known anti-apartheid songs such as "Soweto Blues" and "Bring Him Back Home". He also had a number-one US pop hit in 1968 with his version of "Grazing in the Grass". He died on 23rd January 2018.

Masekela was born in the township of KwaGuqa in Witbank to Thomas Selena Masekela, who was a health inspector and sculptor and his wife, Pauline Bowers Masekela, a social worker. His young sister Barbara Masekela is a poet, educator and ANC activist. As a child, he began singing and playing piano and was largely raised by his grandmother, who ran an illegal bar for miners. At the age of 14, after seeing the 1950 film Young Man with a Horn (in which Kirk Douglas plays a character modelled on American jazz cornetist Bix Beiderbecke), Masekela took up playing the trumpet. His first trumpet was bought for him from a local music store by Archbishop Trevor Huddleston, the anti-apartheid chaplain at St. Peter's Secondary School now known as St. Martin's School (Rosettenville).

Huddleston asked the leader of the then Johannesburg "Native" Municipal Brass Band, Uncle Sauda, to teach Masekela the rudiments of trumpet playing. Masekela quickly mastered the instrument. Soon, some of his schoolmates also became interested in playing instruments, leading to the formation of the Huddleston Jazz Band, South Africa's first youth orchestra. When Louis Armstrong heard of this band from his friend Huddleston he sent one of his own trumpets as a gift for Hugh. By 1956, after leading other ensembles, Masekela joined Alfred Herbert's African Jazz Revue.

From 1954, Masekela played music that closely reflected his life experience. The agony, conflict, and exploitation South Africa faced during the 1950s and 1960s inspired and influenced him to make music and also spread political change. He was an artist who in his music vividly portrayed the struggles and sorrows, as well as the joys and passions of his country. His music protested about apartheid, slavery, government; the hardships individuals were living. Masekela reached a large population that also felt oppressed due to the country's situation.

Following a Manhattan Brothers tour of South Africa in 1958, Masekela wound up in the orchestra of the musical King Kong, written by Todd Matshikiza. King Kong was South Africa's first blockbuster theatrical success, touring the country for a sold-out year with Miriam Makeba and the Manhattan Brothers' Nathan Mdledle in the lead. The musical later went to London's West End for two years.

At the end of 1959, Dollar Brand (later known as Abdullah Ibrahim), Kippie Moeketsi, Makhaya Ntshoko, Johnny Gertze and Hugh formed the Jazz Epistles, the first African jazz group to record an LP. They performed to record-breaking audiences in Johannesburg and Cape Town through late 1959 to early 1960.

Following the 21 March 1960 Sharpeville massacre—where 69 protestors were shot dead in Sharpeville, and the South African government banned gatherings of ten or more people—and the increased brutality of the Apartheid state, Masekela left the country. He was helped by Trevor Huddleston and international friends such as Yehudi Menuhin and John Dankworth, who got him admitted into London's Guildhall School of Music in 1960. During that period, Masekela visited the United States, where he was befriended by Harry Belafonte. After securing a scholarship back in London, he moved to the United States to attend the Manhattan School of Music in New York, where he studied classical trumpet from 1960 to 1964. In 1964, Mariam Makeba and Masekela were married, divorcing two years later.

He had hits in the United States with the pop jazz tunes "Up, Up and Away" (1967) and the number-one smash "Grazing in the Grass" (1968), which sold four million copies. He also appeared at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and was subsequently featured in the film Monterey Pop by D. A. Pennebaker. In 1974, Masekela and friend Stewart Levine organised the Zaire 74 music festival in Kinshasa set around the Rumble in the Jungle boxing match.

He played primarily in jazz ensembles, with guest appearances on recordings by The Byrds ("So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star" and "Lady Friend") and Paul Simon ("Further to Fly"). In 1984, Masekela released the album Techno Bush; from that album, a single entitled "Don't Go Lose It Baby" peaked at number two for two weeks on the dance charts.[19] In 1987, he had a hit single with "Bring Him Back Home". The song became enormously popular, and turned into an unofficial anthem of the anti-apartheid movement and an anthem for the movement to free Nelson Mandela.

A renewed interest in his African roots led Masekela to collaborate with West and Central African musicians, and finally to reconnect with Southern African players when he set up with the help of Jive Records a mobile studio in Botswana, just over the South African border, from 1980 to 1984. Here he re-absorbed and re-used mbaqanga strains, a style he continued to use following his return to South Africa in the early 1990s.

In 1985 Masekela founded the Botswana International School of Music (BISM), which held its first workshop in Gaborone in that year. The event, still in existence, continues as the annual Botswana Music Camp, giving local musicians of all ages and from all backgrounds the opportunity to play and perform together. Masekela taught the jazz course at the first workshop, and performed at the final concert.

Also in the 1980s, Masekela toured with Paul Simon in support of Simon's album Graceland, which featured other South African artists such as Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Miriam Makeba, Ray Phiri, and other elements of the band Kalahari, which was co-founded by guitarist Banjo Mosele and which backed Masekela in the 1980s. As well as recording with Kalahari, he also collaborated in the musical development for the Broadway play, Sarafina!

In 2003, he was featured in the documentary film Amandla!: A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony. In 2004, he released his autobiography, Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela, co-authored with journalist D. Michael Cheers, which detailed Masekela's struggles against apartheid in his homeland, as well as his personal struggles with alcoholism from the late 1970s to the 1990s. In this period, he migrated, in his personal recording career, to mbaqanga, jazz/funk, and the blending of South African sounds, through two albums he recorded with Herb Alpert, and solo recordings, Techno-Bush (recorded in his studio in Botswana), Tomorrow (featuring the anthem "Bring Him Back Home"), Uptownship (a lush-sounding ode to American R&B), Beatin' Aroun de Bush, Sixty, Time, and Revival. His song "Soweto Blues", sung by his former wife, Miriam Makeba, is a blues/jazz piece that mourns the carnage of the Soweto riots in 1976. He also provided interpretations of songs composed by Jorge Ben, Antônio Carlos Jobim, Caiphus Semenya, Jonas Gwangwa, Dorothy Masuka, and Fela Kuti.

In 2006 Masekela was described by Michael A. Gomez, professor of history and Middle Eastern and Islamic studies at New York University as "the father of South African jazz." In 2009, Masekela released the album Phola (meaning "to get well, to heal"), his second recording for 4 Quarters Entertainment/Times Square Records. It includes some songs he wrote in the 1980s but never completed, as well as a reinterpretation of "The Joke of Life (Brinca de Vivre)", which he recorded in the mid-1980s. From October 2007, he was a board member of the Woyome Foundation for Africa.

In 2010, Masekela was featured, with his son Selema Masekela, in a series of videos on ESPN. The series, called Umlando – Through My Father's Eyes, was aired in 10 parts during ESPN's coverage of the FIFA World Cup in South Africa. The series focused on Hugh's and Selema's travels through South Africa. Hugh brought his son to the places he grew up. It was Selema's first trip to his father's homeland. On 3 December 2013, Masekela guested with the Dave Matthews Band in Johannesburg, South Africa. He joined Rashawn Ross on trumpet for "Proudest Monkey" and "Grazing in the Grass". In 2016, at Emperors Palace, Johannesburg, Masekela and Abdullah Ibrahim performed together for the first time in 60 years, reuniting the Jazz Epistles in commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the historic 16 June 1976 youth demonstrations.

Source: Wikipedia

Hugh Ramapolo Masekela was a South African trumpeter, flugelhornist, cornetist, singer and composer who has been described as "the father of South African jazz". Masekela was known for his jazz compositions and for writing well-known anti-apartheid songs such as "Soweto Blues" and "Bring Him Back Home". He also had a number-one US pop hit in 1968 with his version of "Grazing in the Grass". He died on 23rd January 2018.

Masekela was born in the township of KwaGuqa in Witbank to Thomas Selena Masekela, who was a health inspector and sculptor and his wife, Pauline Bowers Masekela, a social worker. His young sister Barbara Masekela is a poet, educator and ANC activist. As a child, he began singing and playing piano and was largely raised by his grandmother, who ran an illegal bar for miners. At the age of 14, after seeing the 1950 film Young Man with a Horn (in which Kirk Douglas plays a character modelled on American jazz cornetist Bix Beiderbecke), Masekela took up playing the trumpet. His first trumpet was bought for him from a local music store by Archbishop Trevor Huddleston, the anti-apartheid chaplain at St. Peter's Secondary School now known as St. Martin's School (Rosettenville).

Huddleston asked the leader of the then Johannesburg "Native" Municipal Brass Band, Uncle Sauda, to teach Masekela the rudiments of trumpet playing. Masekela quickly mastered the instrument. Soon, some of his schoolmates also became interested in playing instruments, leading to the formation of the Huddleston Jazz Band, South Africa's first youth orchestra. When Louis Armstrong heard of this band from his friend Huddleston he sent one of his own trumpets as a gift for Hugh. By 1956, after leading other ensembles, Masekela joined Alfred Herbert's African Jazz Revue.

From 1954, Masekela played music that closely reflected his life experience. The agony, conflict, and exploitation South Africa faced during the 1950s and 1960s inspired and influenced him to make music and also spread political change. He was an artist who in his music vividly portrayed the struggles and sorrows, as well as the joys and passions of his country. His music protested about apartheid, slavery, government; the hardships individuals were living. Masekela reached a large population that also felt oppressed due to the country's situation.

Following a Manhattan Brothers tour of South Africa in 1958, Masekela wound up in the orchestra of the musical King Kong, written by Todd Matshikiza. King Kong was South Africa's first blockbuster theatrical success, touring the country for a sold-out year with Miriam Makeba and the Manhattan Brothers' Nathan Mdledle in the lead. The musical later went to London's West End for two years.

At the end of 1959, Dollar Brand (later known as Abdullah Ibrahim), Kippie Moeketsi, Makhaya Ntshoko, Johnny Gertze and Hugh formed the Jazz Epistles, the first African jazz group to record an LP. They performed to record-breaking audiences in Johannesburg and Cape Town through late 1959 to early 1960.

Following the 21 March 1960 Sharpeville massacre—where 69 protestors were shot dead in Sharpeville, and the South African government banned gatherings of ten or more people—and the increased brutality of the Apartheid state, Masekela left the country. He was helped by Trevor Huddleston and international friends such as Yehudi Menuhin and John Dankworth, who got him admitted into London's Guildhall School of Music in 1960. During that period, Masekela visited the United States, where he was befriended by Harry Belafonte. After securing a scholarship back in London, he moved to the United States to attend the Manhattan School of Music in New York, where he studied classical trumpet from 1960 to 1964. In 1964, Mariam Makeba and Masekela were married, divorcing two years later.

He had hits in the United States with the pop jazz tunes "Up, Up and Away" (1967) and the number-one smash "Grazing in the Grass" (1968), which sold four million copies. He also appeared at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and was subsequently featured in the film Monterey Pop by D. A. Pennebaker. In 1974, Masekela and friend Stewart Levine organised the Zaire 74 music festival in Kinshasa set around the Rumble in the Jungle boxing match.

He played primarily in jazz ensembles, with guest appearances on recordings by The Byrds ("So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star" and "Lady Friend") and Paul Simon ("Further to Fly"). In 1984, Masekela released the album Techno Bush; from that album, a single entitled "Don't Go Lose It Baby" peaked at number two for two weeks on the dance charts.[19] In 1987, he had a hit single with "Bring Him Back Home". The song became enormously popular, and turned into an unofficial anthem of the anti-apartheid movement and an anthem for the movement to free Nelson Mandela.

A renewed interest in his African roots led Masekela to collaborate with West and Central African musicians, and finally to reconnect with Southern African players when he set up with the help of Jive Records a mobile studio in Botswana, just over the South African border, from 1980 to 1984. Here he re-absorbed and re-used mbaqanga strains, a style he continued to use following his return to South Africa in the early 1990s.

In 1985 Masekela founded the Botswana International School of Music (BISM), which held its first workshop in Gaborone in that year. The event, still in existence, continues as the annual Botswana Music Camp, giving local musicians of all ages and from all backgrounds the opportunity to play and perform together. Masekela taught the jazz course at the first workshop, and performed at the final concert.

Also in the 1980s, Masekela toured with Paul Simon in support of Simon's album Graceland, which featured other South African artists such as Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Miriam Makeba, Ray Phiri, and other elements of the band Kalahari, which was co-founded by guitarist Banjo Mosele and which backed Masekela in the 1980s. As well as recording with Kalahari, he also collaborated in the musical development for the Broadway play, Sarafina!

In 2003, he was featured in the documentary film Amandla!: A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony. In 2004, he released his autobiography, Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela, co-authored with journalist D. Michael Cheers, which detailed Masekela's struggles against apartheid in his homeland, as well as his personal struggles with alcoholism from the late 1970s to the 1990s. In this period, he migrated, in his personal recording career, to mbaqanga, jazz/funk, and the blending of South African sounds, through two albums he recorded with Herb Alpert, and solo recordings, Techno-Bush (recorded in his studio in Botswana), Tomorrow (featuring the anthem "Bring Him Back Home"), Uptownship (a lush-sounding ode to American R&B), Beatin' Aroun de Bush, Sixty, Time, and Revival. His song "Soweto Blues", sung by his former wife, Miriam Makeba, is a blues/jazz piece that mourns the carnage of the Soweto riots in 1976. He also provided interpretations of songs composed by Jorge Ben, Antônio Carlos Jobim, Caiphus Semenya, Jonas Gwangwa, Dorothy Masuka, and Fela Kuti.

In 2006 Masekela was described by Michael A. Gomez, professor of history and Middle Eastern and Islamic studies at New York University as "the father of South African jazz." In 2009, Masekela released the album Phola (meaning "to get well, to heal"), his second recording for 4 Quarters Entertainment/Times Square Records. It includes some songs he wrote in the 1980s but never completed, as well as a reinterpretation of "The Joke of Life (Brinca de Vivre)", which he recorded in the mid-1980s. From October 2007, he was a board member of the Woyome Foundation for Africa.

In 2010, Masekela was featured, with his son Selema Masekela, in a series of videos on ESPN. The series, called Umlando – Through My Father's Eyes, was aired in 10 parts during ESPN's coverage of the FIFA World Cup in South Africa. The series focused on Hugh's and Selema's travels through South Africa. Hugh brought his son to the places he grew up. It was Selema's first trip to his father's homeland. On 3 December 2013, Masekela guested with the Dave Matthews Band in Johannesburg, South Africa. He joined Rashawn Ross on trumpet for "Proudest Monkey" and "Grazing in the Grass". In 2016, at Emperors Palace, Johannesburg, Masekela and Abdullah Ibrahim performed together for the first time in 60 years, reuniting the Jazz Epistles in commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the historic 16 June 1976 youth demonstrations.

Source: Wikipedia